Innovative virtual reality training could prevent real life injuries in construction industry

What if you could learn from your mistakes before they happen?

In high-risk industries like construction and electrical work, a single error can be life-altering or deadly. Workers take safety trainings, but long days and weeks of hard work around dangerous equipment can numb professionals to hazards — a well-known jobsite phenomenon that researchers call “risk habituation.”

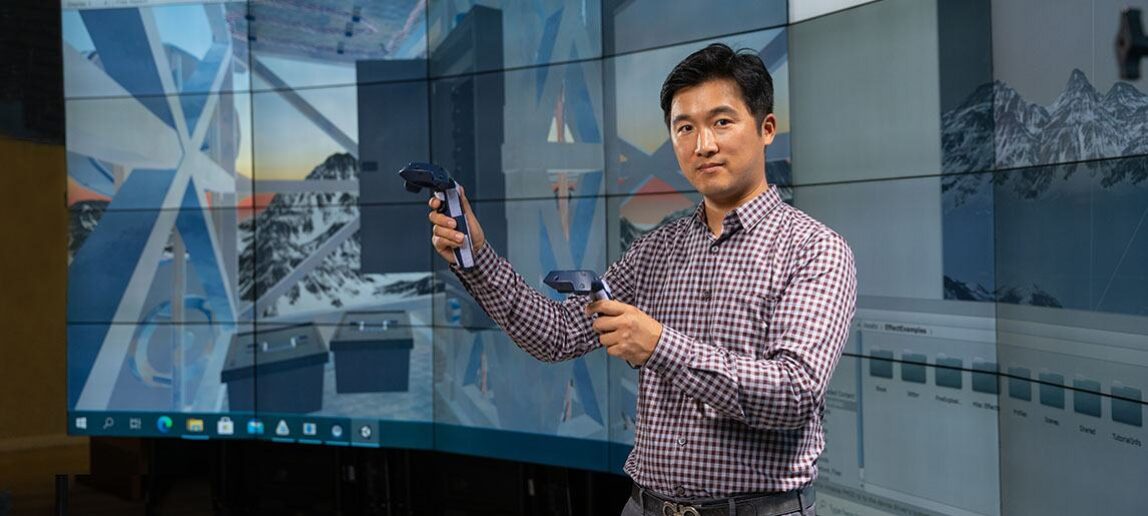

To help prevent jobsite accidents and save lives by interrupting potentially dangerous, habituated jobsite behavior, Ryan Ahn, Texas A&M associate professor of construction science, is developing a research-based, virtual reality training environment that doesn’t expose workers to real-life risk.

Funded by a $750,000 National Science Foundation grant, Ahn and Brian Anderson, Texas A&M associate professor of psychological and brain sciences, are creating virtual reality environments that simulate accidents, and provide unpleasant, but not dangerous, sensory feedback to trainees. They will then study how the training impacts trainees’ risk perception and their attitudes about jobsite safety.

Learned Risk Behavior

Ahn has seen firsthand how accidents can affect workers and their families.

“My uncle was an employee at my dad’s construction company and was badly injured doing electrical work,” Ahn said. “He was in the hospital for a long time.”

Ahn’s father built the family home and headed an electrical contracting company during Ahn’s youth, which inspired him to choose architecture as his college major.

However, he quickly learned that art and design wasn’t his favorite work. Because he also had an interest in technology, he switched majors to construction science, and discovered his passion for using emerging tech to improve construction safety.

Electricians, like Ahn’s uncle, have dangerous jobs. Because they work at heights and with high voltage, they encounter high risk every day.

Ahn said that while these workers are highly trained and skilled, they often fall prey to “risk habituation,” which causes many occupational workers to unintentionally expose themselves to hazards.

“There are a lot of high-risk hazards on a jobsite, and on the first day, these workers are informed of them in detail,” Ahn said. “But they work for a long time and find the hazards aren’t having a direct impact on them, so they start to ignore them.”

Ahn said once workers do something against safety standards and nothing happens, it can feel like there isn’t as much risk anymore and they’re far more likely to repeat the behavior.

“You do it the wrong way so many times and nothing happens, so you think it’s safe,” Ahn said. “That is when injury happens.”

Background Noise

Another contributing factor for workplace safety accidents is “sensory level habituation,” which happens when professionals who work close to safety equipment end up tuning out audible warning signals simply because they acclimate to the sounds.

“We’re investigating how much these workers are habituated to those sounds,” Ahn said. “By doing a psycho-physical assessment on workers with three or more years of experience in the field, we can see if the brain is responding to those sounds or if they’re just hearing them as background noise.”

Breaking the Habit

Similar to how a child is more careful to not touch a stove after burning their hand, Ahn says a worker who has experienced an accident becomes more alert of the dangerous behavior.

Ahn hopes to create a similarly powerful and long-lasting memory without endangering a person’s body.

To do this, Ahn and his team created a virtual, simulated working environment. The first scenario is a pedestrian roadway worker doing a job around heavy machinery.

A subject who enters the training is given an assignment in the virtual jobsite and is monitored as they work via eye movement tracking technology. Most subjects start habituating, or stop paying attention to safety signals, after just 15–20 minutes into the simulation, he said. When the worker stops paying attention to safety signals or being aware of what’s around them, trainers expose them to consequences.

“We run them over with a streamroller,” Ahn said.

Subjects experience the visual sensation of the accident in virtual reality and punitive feedback via sound, vibration and electrical impulses from a backpack that stimulates their nerves.

The shock is harmless, but the combined experience creates a more vivid simulation and, hopefully, a more sustained memory impact, said Ahn.

Changing Behaviors

The team did a version of the experiment where some subjects experienced an accident and others, who were more alert to signals, did not. A month later, they brought back both groups and found that those who didn’t experience the accident habituated much more quickly than their steamrolled counterparts.

“They got complacent,” Ahn said. “Later we will get feedback from their safety manager to see if their behavior has improved.”

Ahn hopes his VR training system can eventually replace the existing safety programs workers go through, which are classroom-based lecture programs where certified instructors talk about common hazards of jobsites and how to avoid them.

“The workers are required to take those trainings repeatedly,” Ahn said. “The problem is that while it delivers the knowledge and refreshes it, it is not changing the behavior of the workers.”

By presenting their behaviors in VR and doing an intervention, Ahn said he believes that they can actually change behaviors and improve jobsite safety.